Something peculiar is happening in the job markets of Europe. University graduates clutching degrees in media studies queue for unpaid internships at start-ups, whilst electricians are earning more in a week than many office workers see in a month.

In Switzerland, a plumber can pocket 5,500 euros monthly. German electricians with a few years’ experience easily clear 3,500 euros. Even the humblest Norwegian heating engineer laughs all the way to the bank.

Yet mention ‘vocational training’ to most European parents and watch their faces crumple. The very phrase conjures images of greasy overalls and diminished prospects—anything but the reality of modern skilled trades, where workers programme sophisticated building systems and command premium wages for expertise that no algorithm can replicate.

The numbers tell the story plainly enough. Across the EU, four in five businesses cannot find workers with the right skills. Brussels has identified 42 occupations in shortage, most of them involving tools rather than PowerPoint presentations. Meanwhile, the continent loses a million workers annually to retirement—a haemorrhaging of talent that university lecture halls cannot possibly staunch.

The great European snobbery

This paradox springs from a cultural mythology that equates intelligence with avoiding physical work. For generations, European families have measured success by how far their children’s careers take them from anything requiring callused hands. A law degree gathering dust? Respectable. A thriving plumbing business? Somewhat embarrassing at dinner parties.

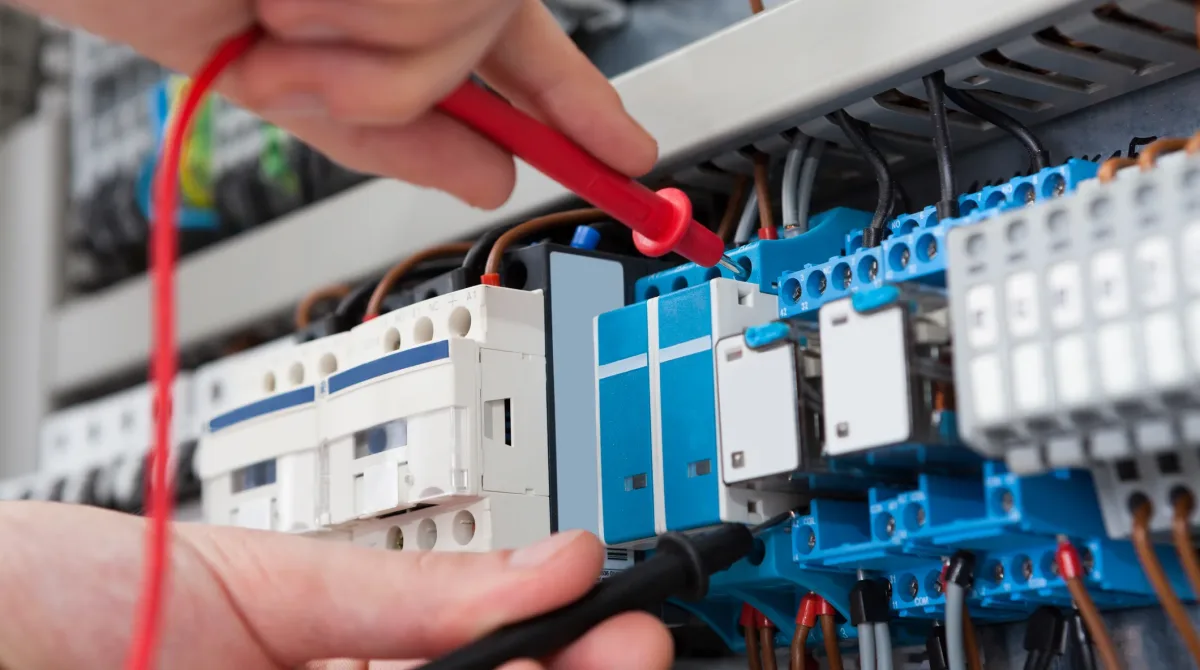

The irony runs deeper than mere social climbing. Many trades now demand more cognitive horsepower than the average office job. Modern electricians don’t just twist wires—they programme complex building management systems that would befuddle most consultants. Today’s heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) technicians diagnose problems using computerised equipment more sophisticated than the tools available to surgeons a generation ago.

Nevertheless, the prejudice persists with stunning tenacity. Even in Germany, where apprenticeships enjoy cultural reverence, researchers worry about an ‘educational schism‘ that treats vocational training as inherently inferior to university study. France remains particularly afflicted by this delusion, with families preferring their children struggle through mediocre university programmes rather than excel in profitable trades.

The madness becomes apparent when we consider what artificial intelligence cannot do. Lawyers fret about algorithms writing contracts; journalists worry about ChatGPT stealing their bylines; accountants eye the spreadsheet software nervously. But no robot will unclog your pipes at midnight, rewire your grandmother’s cottage, or install solar panels on a wind-swept roof. Physical intelligence—the kind that solves problems through touch, observation, and hard-won experience—remains gloriously human.

Where Europe gets it right

Switzerland offers a masterclass in getting vocational education right. The Swiss long ago grasped that different kinds of intelligence deserve different kinds of respect. Their apprenticeship system rests on the principle that vocational training and university education are ‘different but equal’—a revolutionary concept that seems blindingly obvious once stated.

The Swiss vocational baccalaureate exemplifies this thinking. Introduced in 1993, it allows apprentices to access universities of applied sciences without abandoning their practical training. The result? Bright students don’t flee the trades for fear of hitting educational dead ends. Instead, they can become master craftspeople and professors—sometimes both.

Germany’s dual system works similar magic through different means. Nearly half the German population holds vocational qualifications, with apprentices splitting time between workshops and classrooms. The key lies in coordination: employers, trade unions, and government work together rather than pursuing separate agendas. When training matches labour market needs, everyone benefits.

Austria also deserves credit for its own innovation—the berufsbildende höhere Schule system that marries vocational training with university entrance qualifications. These hybrid approaches point toward solutions for countries trapped by rigid educational hierarchies.

The rest catch up slowly

Most of Europe, alas, remains stubbornly attached to educational apartheid. Vocational programmes languish as dumping grounds for students deemed unfit for ‘proper’ subjects. Career counsellors, often refugees from failed academic careers themselves, steer promising youngsters toward universities regardless of aptitude or interest.

The European Commission recognises the crisis. Its ‘Skills Union’ initiative, introduced last year, promises massive investment in training and skills development. Companies are starting to act independently: Vonovia, a real estate giant, recently opened a gleaming training centre in Berlin, complete with high-tech workshops and courses in everything from heat pump installation to customer service.

But policy initiatives cannot overcome cultural cringe. Parents who spent their youth escaping manual labour cannot easily embrace it for their children. Teachers who chose academia often know little about modern trade realities. Until Europeans abandon the notion that working with one’s hands indicates intellectual failure, the skills shortage will persist.

What success looks like

The path forward requires abandoning false hierarchies. A master carpenter solves spatial puzzles that would stump most architects. A skilled welder manipulates materials at the molecular level with precision a chemist might envy. These are not consolation careers for the academically challenged—they are sophisticated professions requiring continuous learning and creative problem-solving.

European education systems must showcase this reality. Career guidance should present accurate information about earning potential rather than perpetuating myths about university graduates’ automatic superiority. Schools need partnerships with modern employers, not just traditional academic institutions.

Most importantly, Europeans must rediscover respect for making things. The electrician who keeps the lights on, the plumber who maintains civilisation’s most basic infrastructure, the roofer who shields families from the elements—these people perform essential work that deserves recognition, not condescension.

The infrastructure crisis looms

The problem extends beyond individual career choices. Europe faces enormous infrastructure challenges: the green energy transition, aging populations requiring new housing, and increased defence spending following geopolitical upheavals. All depend on skilled manual workers.

Germany already reports 450,000 unfilled construction positions. Across the continent, businesses turn away work because they lack qualified staff. This represents not just missed opportunities but genuine threats to European competitiveness.

Consider the mathematics: if Europeans continue channelling talent toward oversaturated white-collar fields whilst ignoring skilled trades, infrastructure will deteriorate and energy transitions will stall. Countries that solve this puzzle first—by embracing the dignity of skilled work—will secure lasting advantages.

A matter of survival

Switzerland and, to a lesser extent, Germany prove that respecting trades strengthens rather than weakens societies. They recognise that their economies need bright young people who see apprenticeships as stepping stones rather than dead ends. Other European nations must learn this lesson quickly or face consequences their university-obsessed cultures have not yet imagined.

The alternative grows clearer each year: a continent where brilliant minds compete for precarious gig work whilst essential infrastructure crumbles for want of people willing to fix it. That represents the ultimate educational failure—producing graduates who can analyse anything but cannot build the world they wish to inhabit.

Europe’s choice simple: embrace the nobility of skilled work or watch more vital systems break down. The plumbers, electricians, and builders are waiting. The question is whether European pride will let them save the day.

Photo: Dreamstime.