Russia’s invasion has caused one of Europe’s largest cultural heritage losses since World War II. The systematic removal of museum collections from occupied territories forms part of Russia’s cultural appropriation policy. Ukrainian museums were left vulnerable—without evacuation procedures, state support, or basic instructions.

Russia is now attempting to legitimise these thefts by creating ‘twin’ Ukrainian museums in occupied territories, rewriting inventories, and holding exhibitions in Crimea, Taganrog, and even abroad. The path to restitution is just beginning and requires comprehensive solutions.

Museums abandoned during occupation

Under museum lights in occupied Simferopol’s Central Museum of Tavrida, paintings by prominent Ukrainian artists—formerly exhibits at the Kherson Art Museum—are displayed with no mention of their forcible removal in November 2022.

In Mariupol, valuable works disappeared from the Local History Museum, including Arkhip Kuindzhi’s paintings valued at over one million US dollars each and Aivazovsky’s works worth up to 800,000 euros. From Melitopol, ancient weapons and fourth-century BC Scythian gold were taken. These treasures ended up in Crimea, occupied Donbas, or abroad—stripped of their identity and origin.

As of May 2025, Ukraine’s Ministry of Culture confirms looting from at least 46 museums in occupied territories. Experts estimate more than 134,000 stolen museum objects worth over 200 million euros.

Why weren’t frontline museums evacuated despite warning signs from 2014, when Russians looted museums in occupied Donbas and Crimea?

“The government knew the risks but lacked legislative and logistical tools for rapid implementation,” explains Oleksandr Tkachenko, Ukraine’s former Minister of Culture. The ministry requested support from security services but received no approval due to security concerns and the absence of a coordinated plan.

“We waited for instructions until the last minute,” recalls Leila Ibragimova, director of the Melitopol Museum of Local Lore. “At night, we buried ancient weapons and Scythian gold under the museum. They found it anyway.”

Museum workers had no transportation, security, or clear instructions. According to Mariia Sliuta, exiled director of the Mariupol Museum, “Each institution improvised on its own. There was no single coordinator responsible for this area.”

Russia’s legalisation of stolen artifacts

Russia is systematically attempting to classify stolen items as its own cultural heritage by creating ‘twin’ Ukrainian museums under Russian jurisdiction, where looted objects are inventoried and displayed.

“Russia is creating a legal wrapper for cultural looting,” explains human rights activist Andriy Lutsyk. “They register institutions like the Kherson Museum in Simferopol and ‘temporarily store’ the loot there.”

During wartime, Ukrainian museums should be protected under the 1954 Hague Convention for Cultural Property Protection in Armed Conflict. However, Russia disregards these international obligations.

The stolen objects are entered into Russian inventory catalogs without mentioning their Ukrainian origin, effectively converting them into Russian cultural heritage in official documentation.

Vitaliy Tytych, chairman of the Lemkin Society, notes: “Russia hasn’t signed the second protocol of the Hague Convention, which would establish liability. This lets them avoid direct sanctions. We’re dealing with systematic identity destruction through culture.”

Exhibition and trafficking of stolen items

Russian museums have begun displaying Ukrainian exhibits as part of a “new regional heritage”—an attempt to integrate stolen works into the Russian cultural canon.

In 2023, Taganrog hosted an exhibition featuring works from Mariupol’s Kuindzhi Art Museum presented as “gifts from the liberated city,” with no reference to their Ukrainian origin.

In April 2025, Uzbekistan’s State Museum of History opened ‘The Heritage of the Black Sea Region’, an exhibition organised with Russia’s Ministry of Culture and the Hermitage Museum. According to Ukraine’s Institute of Archaeology, this included copies and likely originals of Scythian gold matching items stolen from the Melitopol Museum in 2022. Ukraine wasn’t mentioned in any exhibition materials.

Beyond official ‘evacuations’, individual thefts by Russian militants have occurred. These artifacts appear at closed auctions, on the dark web, or through the gray art market.

Ukraine’s response and international cooperation

In 2023, the Ukrainian Heritage Monitoring Lab (HeMo) and SUCHO, an initiative of over 1,500 international volunteers who are collaborating online to digitise and preserve Ukrainian cultural heritage transferred over 2,000 items from Ukrainian inventory books to the Art Loss Register, including digital collections from museums in Mariupol, Melitopol, and Kherson. Some documentation was forwarded to Interpol through Ukraine’s Ministry of Culture.

“Unfortunately, cataloging is our only response so far,” says Maria Zadorozhna, a heritage protection specialist. “Without clear digital records, we lose our international voice.”

Ukraine has increased cooperation with UNESCO, Interpol, Europol, the Art Loss Register, EU customs, and cultural institutions worldwide. A digital ‘Stolen Heritage’ catalogue has been created as a register of internationally wanted objects.

However, Ukraine still lacks a national archive of inventory books, a unified database of at-risk objects, and a specialized institution for international restitution.

The path forward

As of 2025, dozens of museums in Sumy, Kharkiv, Zaporizhzhia, and Dnipro regions remain vulnerable. Most lack approved evacuation plans or access to centralized logistical solutions.

Ukraine’s Ministry of Culture reports that 540,942 items from 63 institutions have been evacuated since the invasion began, but most movements occurred in 2022, primarily from Kyiv. The state faces a severe shortage of adequate storage facilities—only 900 of the required 19,000 cubic meters are available.

By comparison, Germany has legally required museums to maintain preservation and relocation plans since World War II. Italian cultural protection includes special warehouses, protected areas, and teams trained for evacuations.

Without legislative changes, infrastructure development, and adequate staffing, Ukraine’s cultural heritage remains at risk of further losses in the event of renewed offensive operations.

The article was co-written by Olena Solodovnikova and with the support of a grant from the VZW Journalism Fund Europe, ‘Strengthening democracy through independent cross-border investigative journalism’.

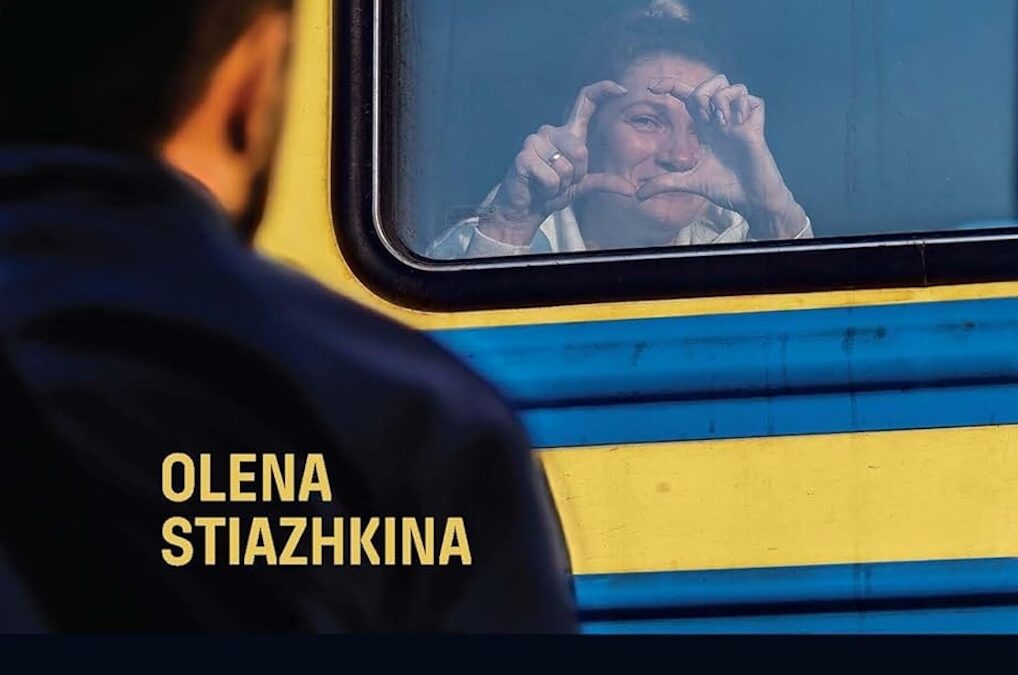

Photo: Dreamstime.