On January 15, Wikipedia will celebrate its 25th birthday with the sort of fanfare typically reserved for minor provincial saints. Expect earnest blog posts from the Wikimedia Foundation, and the standard media reflection pieces about how remarkable it is that an encyclopaedia written by unpaid strangers has survived this long.

What you will not see is anyone reckoning with the fact that the world’s most consulted reference work has become critical infrastructure that nobody controls—and everyone wants to.

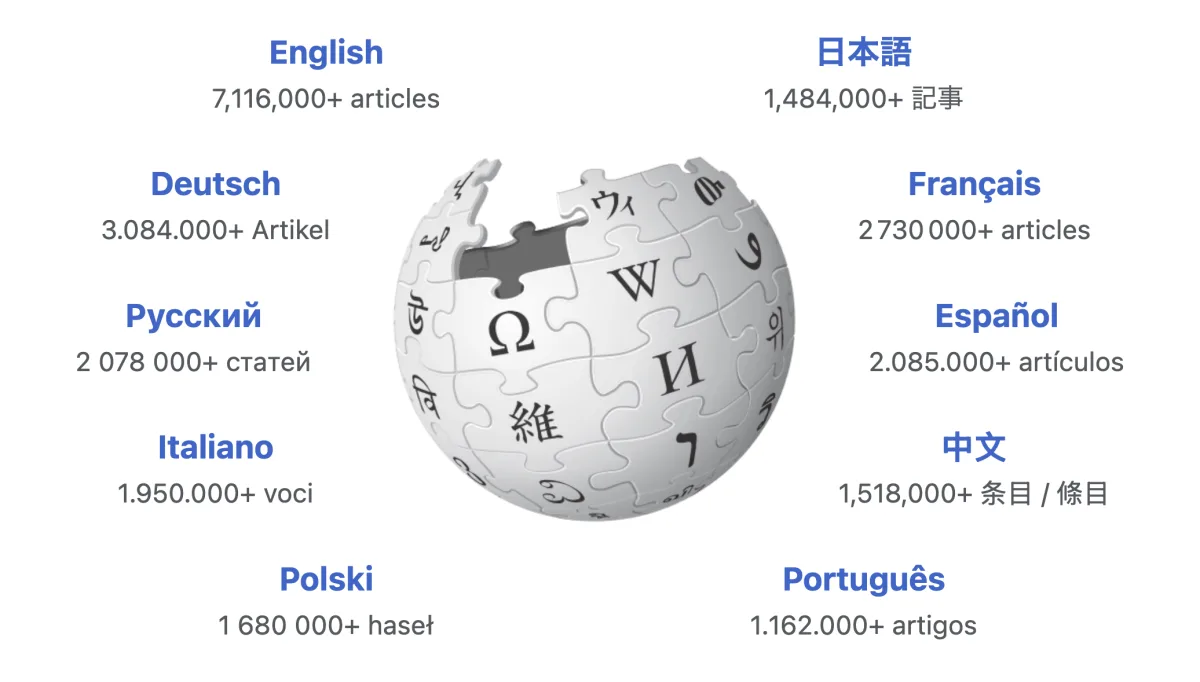

Wikipedia’s English edition includes 7.1 million articles across 66 million pieces in 300-plus languages. Nearly 250,000 volunteer editors made 79 million changes last year. The site receives more than a billion unique visitors monthly. Google’s Knowledge Panels pull from it. Alexa and Siri cite it. And virtually every large language model released since 2018—from GPT to Claude—has trained on it.

That last point matters more than most people grasp. When OpenAI or Anthropic scrapes the web to build their models, Wikipedia provides the scaffolding. Its citations offer verification pathways. Its neutral-point-of-view policy shapes how models present contested facts. Its edit histories teach machines about consensus formation. The Wikimedia Foundation acknowledged in 2023 that “without access to the information on Wikipedia, AI models become significantly less accurate, diverse, and verifiable”. In other words: the knowledge commons has become training data infrastructure.

Nobody owns this infrastructure in the conventional sense. The Wikimedia Foundation, a non-profit registered in California, operates the servers and employs roughly 700 staff. But it does not own the content—that belongs to the contributors under Creative Commons licences. Nor does it control editorial policy—that emerges from consensus among the volunteer editing community. The foundation cannot simply decree what Wikipedia says about Taiwan or transgender rights or the Trump presidency. It maintains the platform; the crowd writes the encyclopaedia.

The scramble for narrative control

This creates a peculiar strategic vulnerability. When Chinese researchers discussed “cultivating influential editors on the wiki platform” who “adhere to socialist values”, they understood what many Western governments have not: whoever shapes Wikipedia shapes the substrate of machine intelligence. The same logic applies to Saudi Arabia’s alleged infiltration of Arabic Wikipedia’s administrator ranks, or Iran’s ministry-level meetings with Persian Wikipedia editors, or Russia’s escalating threats against editors covering the Ukrainian invasion.

The attacks are getting sophisticated. Not crude vandalism—automated bots catch that within minutes—but patient campaigns to shift language, prune citations, and reframe narratives. A 2024 study warned that Wikipedia faces “sustainability challenges” as LLMs threaten the incentive structure that keeps volunteers editing. Why contribute knowledge that chatbots will summarise (without attribution) for users who never visit the site?

The bigger threat is capture. In April 2025, acting US Attorney Ed Martin accused the Wikimedia Foundation of “allowing foreign actors to manipulate information”. Twenty-three members of Congress demanded explanations about “anti-Israel bias”. The Heritage Foundation announced plans to “identify and target” editors. Elon Musk encouraged users to abandon the site entirely. None of these critics proposed solutions; all demanded control.

Why chaos works better than order

Nevertheless, Wikipedia’s governance model—messy, consensus-driven, occasionally captured by obsessive partisans—arguably works better than any centralised alternative would. Its weakness is also its strength. No government owns it, so no government can simply decree what is true. No company profits from it, so no board can monetise access. The neutral point of view policy, whatever its flaws in execution, at least forces competing factions to justify their edits with sources rather than power.

Consider the corporate alternative. Businesses have spent the past decade trying to build internal ‘knowledge management systems’—Notion wikis, Confluence pages, SharePoint repositories. Most become graveyards within months. Information decays. Links break. The people who wrote the documentation leave the company. What remains is a zombie knowledge base that employees bypass by asking colleagues on Slack.

What companies get wrong about knowledge

Wikipedia avoids this fate through radical transparency. Every edit is logged. Every discussion is public. Every article has a history tab showing exactly how it evolved. This creates natural selection pressure: bad information gets contested, unsourced claims get flagged, and sufficiently contentious articles attract enough scrutiny that partisan edits rarely survive. The system is not perfect—bias persists, particularly on articles edited by small homogeneous groups—but it is self-correcting at scale.

Corporations could learn something here. The problem with traditional knowledge management is not technology but incentives. Wikipedia’s editors contribute because they care about specific topics and enjoy recognition from peers. Corporate knowledge bases fail because nobody’s bonus depends on updating the Q4 2025 sales process documentation. The few successful corporate wikis—usually maintained by obsessive engineers at technical companies—succeed precisely because they adopt Wikipedia’s distributed maintenance model rather than imposing centralised control.

The lesson extends beyond internal documentation. Any organisation dependent on institutional knowledge should worry about what happens when the people carrying that knowledge retire, resign, or simply forget. The ‘living knowledge base’ is not a product to purchase but a culture to cultivate—one where documentation is a shared responsibility and contribution carries status.

The backlash begins

If Wikipedia has solved the technical challenge of distributed knowledge management, it has not solved the political one. The ‘commons backlash’ is coming, and it will not be polite. As AI systems become strategic infrastructure, governments will decide that the datasets feeding them require oversight. Companies already paying billions for compute will resent that their models depend on a free encyclopaedia maintained by volunteers. The temptation to fence the commons—to require licencing, to impose editorial standards, to ‘ensure accuracy’ through official review—will prove irresistible.

This should not come as a surprise. Every knowledge commons that becomes economically valuable eventually gets captured. Academic publishing, once a scholarly gift economy, is now controlled by three corporations extracting 42 per cent profit margins. Medical research, nominally public, hides behind paywalls. Even open-source software, supposedly immune to capture, now depends on corporate-funded foundations and contributor licensing agreements.

Wikipedia has survived 25 years in part because it remained just quirky enough to seem non-threatening. But once everyone from Beijing to Washington recognises it as strategic infrastructure, the pressure to control it will intensify. The choice then becomes stark: either governments and platforms accept that the knowledge substrate of machine intelligence should remain outside commercial and state control, or they do not.

If they do not, the consequences are predictable. Access will be licenced. Edits will require verification. Official truth will supplant crowd-sourced consensus. And everyone who depends on Wikipedia—which is to say, everyone—will pay rent. Not necessarily in currency, though that may come. More likely in narrative control, in whose version of contested events becomes canonical, in which sources count as reliable.

The birthday that matters then is not the 25th but the 30th. That will tell us whether the commons survived or whether we allowed it to be captured because we failed to defend something we took for granted. The infrastructure nobody owns is infrastructure everyone needs. The question is whether that remains true.