Investment banks still organise themselves around countries. So do consulting firms, credit-rating agencies and most institutional investors. They track national GDP. They publish reports on ‘the Polish economy’ and ‘Brazilian market entry strategies’. Never mind that Poland is actually (at least) three different economies—Warsaw’s fintech corridor, Silesia’s automotive clusters and the Baltic logistics belt—moving at completely different speeds. Brazil? More like seven—again, at the very least.

Meanwhile, the smartest capital allocators have stopped caring about national borders. They’re backing regions, provinces and economic corridors instead. Because that’s where growth actually happens now.

National statistics have become useless

Take ‘European growth’. The IMF reckons the continent will expand by 1.5 per cent in 2025. Fine. Except southern German manufacturers are bleeding whilst Nordic digital clusters are thriving. Central European regions are growing at 2.4 per cent—but Prague is accelerating away from the Czech hinterlands at rates that would make Shenzhen jealous. Budapest, too. The ‘European average’ obscures more than it explains.

America looks coherent on paper. In reality, Charlotte ballooned 93 per cent between 2005 and 2024 whilst Detroit withered. China’s coastal zones print money; its interior stagnates. India’s growth is Bengaluru, Hyderabad and Mumbai. Everything else is arithmetic.

Even places that should share a common trajectory don’t. South Carolina’s employment is growing at three per cent annually—the fastest on the East Coast—because Greenville and Charleston built regional incentive structures that bypass federal policy entirely. Greater Grand Rapids keeps outrunning Michigan’s averages on jobs, investment and population growth. Not because of anything happening in Washington or Lansing, but because local actors made it happen.

The tools that matter moved downstairs

National governments still set interest rates and negotiate trade deals. Brilliant. Meanwhile the things that actually determine whether companies invest or workers move—infrastructure, zoning, digital permits, talent visas—migrated to regional and municipal control years ago. Nobody noticed because economists kept staring at central bank press releases.

Special economic zones tell the story. Emerging Europe now hosts 1,150 of them, up from fewer than 100 in 1990. They work, sort of. Analysis shows zones boost local activity over time—except 60 per cent fail outright. National policy can’t predict winners. Success depends on having a port nearby, educated locals and competent regional administrators. All of which vary wildly within the same country.

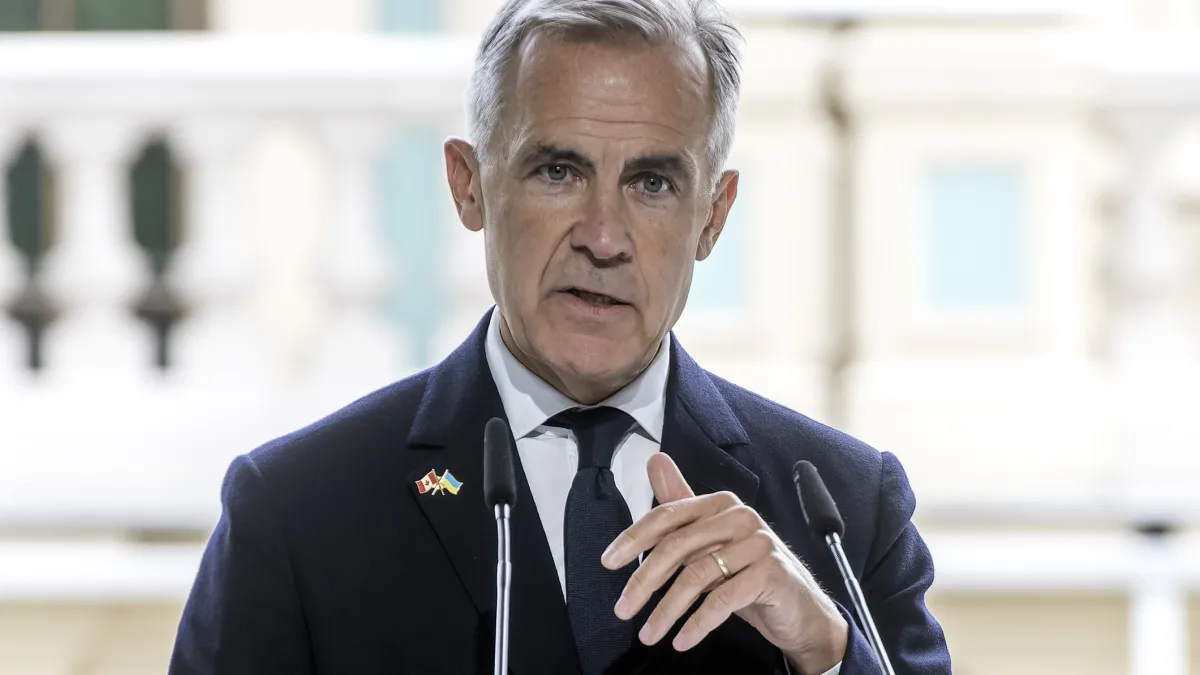

The UAE’s Jebel Ali zone (whose port is pictured above) generated 135,000 jobs and accounts for a fifth of Dubai’s GDP. Bangladesh’s eight export zones created half a million jobs. National governments permitted these. Regional authorities built them.

More to the point: regions move fast. National reform crawls through parliamentary committees, satisfies coalition partners, waits for budget cycles. Provincial governments issue bonds, cut deals with developers, build things. Pittsburgh deployed AI-powered traffic management that slashed travel times 25 per cent whilst Washington was still forming a committee to study whether smart cities deserved a pilot programme.

India added 300 kilometres of metro lines in a single year through state initiatives that ignored New Delhi entirely. Aichi Prefecture launched Japan’s largest innovation hub in 2024 to stem Tokyo’s talent drain—didn’t bother asking the national government for permission first.

Regional actors test things, see what works, scale fast. The centre copies later because constituents demand it.

Corridors are eating borders

Economic geography reorganised itself when nobody was looking. The EU’s Global Gateway programme plans to pour 300 billion euros into infrastructure—not by country, but into 12 African transport corridors meant to function as economic units unto themselves. With their own governance, data-sharing rules, joint institutions. National boundaries optional.

Southeast Asia’s already there. Chinese industrial parks stretch across Cambodia, Vietnam, Thailand and Laos with harmonised regulations that treat national borders as cartographic trivia.

The Johor-Singapore zone operates under joint governance that supersedes Malaysian law whenever convenient. These corridors outlast governments. They’re what investors actually bet on.

Why regions beat nations at reinvention

Provincial governments can’t export their problems elsewhere. Can’t blame external shocks. Can’t hide behind macro narratives. A housing shortage is their housing shortage. Clogged ports are their clogged ports. Regions live with consequences, so they fix things.

This forces a different mode of thinking. National politics lets you pretend that labour markets, housing, transport and energy exist in separate ministries. Regional governance can’t afford that delusion. You see the system because you’re stuck inside it.

Governments treating regional autonomy as a constitutional nuisance are now at a competitive disadvantage. The winners over the next decade will be countries that deliberately empower provinces to act independently—not the ones micromanaging them as administrative subdivisions.

Corporate strategy needs new maps. Site selection shouldn’t track “Polish market entry”. It should track Greater Silesia’s labour mobility, infrastructure spend and governance effectiveness. Supply chains should route around regional capabilities, not sovereign risk ratings.

Investors, meanwhile, should stop pretending national borders matter. South Carolina’s employment growth tells you more than America’s two per cent. Aichi Prefecture’s start-up density matters more than Japan’s stagnation. The outperformers won’t be emerging markets or developed markets. They’ll be emerging regions and corridors that figured out how to reinvent themselves.

Nation-states still monopolise sovereignty. Fair enough. But economic reality migrated to regions years ago. Countries aggregate divergent trajectories. Regions drive actual growth. The sooner capital markets, corporate strategists and development banks internalise that, the better everyone’s returns.

Photo: Dreamstime.